Population Ageing & Global Health

Introduction

For the first time in history, our world is ageing. That is, the number of individuals 65 years and above in the world has caught up and will soon out number children under the age of 5 years.1 This poses a significant global health issue that threatens to impact the healthcare systems, economies, and social structures of nations worldwide.

We will explore the obstacles caused by global population ageing and highlight why this is global health issue that deserves attention and action. But first, it is important to understand how we define a ‘global health’ issue.

Scholar Jeffery Koplan suggests that ‘global health’ has evolved from principals that overlap with ‘public health’—broadly defined as population-based efforts to protect and promote health and wellbeing within a society—and ‘international health’—the application of (public) health interventions within low- and middle-income countries.2 Although all three terms are intimately related by similar founding principals, ‘global health’ evokes a nuance that is necessary to articulate in order for parties to cohesively identify and act on issues.

The defining principal of global health, which separates it from public health and international health, lies within the concepts of ‘stakeholders’ and ‘investors’: whose health and wellbeing is under threat from insults—biological, psychological, or social—or benefiting from intervention; and who is providing the means for those beneficial interventions to be carried out. In public health, both stakeholders and investors are widely domestic; in international health, stakeholders are low- and middle-income countries, but investors are largely high-income countries (e.g. foreign aid).2

However in global health, there is no single stakeholder or investor, and the relationship between the two is not linear. Rather, global health addresses issues surrounding health that affect or are affected by transnational (multinational) circumstances, so that low-, middle- and high-income countries are situated in a network of accountability as both stakeholders and investors.

This essay will attempt to demonstrate that population ageing is an important global health issue by:

- Exploring current trends in population ageing

- Establishing the impacts of global ageing

- Discussing measures to address this issue

Our Globally Ageing Population

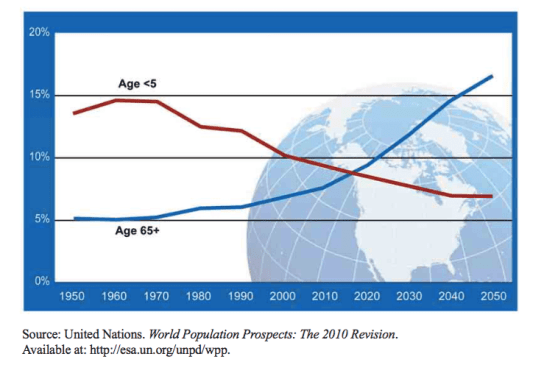

We, as a people, are growing older. Currently, over 520 million people, nearly 10 percent of our global population, are aged 65 or older. This number is due to triple to 1.5 billion by 2050, pushing the proportion closer 20 percent of our current population (Figure 1).1

Figure 1: Young people and Elderly as a Percentage of Global Population Between 1950 and 2050.3

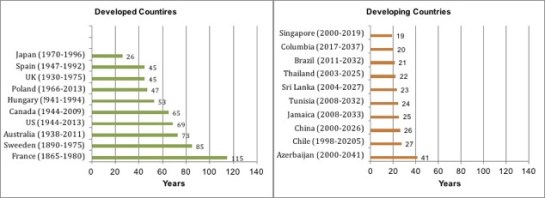

This phenomenon is affecting countries worldwide, regardless of socioeconomic circumstance. Figure 2 depicts the number of years for the population percentage of people aged 65 and above to double (7% to 14%) in both low- and high-income countries.4

Whilst high-income countries have older population profiles that have developed over time, low-income countries currently have the most rapidly ageing populations.1 This ultimately culminates in widespread population ageing that is likely to accelerate.4

Figure 2: Number of years for population to increase from 7 to 14 percent.5

Factors Influencing Population Ageing

Population ageing has largely resulted from a combination of worldwide increases in life expectancy and decreases in fertility rates.

Life Expectancy

Life expectancy has continued to increase in the vast majority of countries across the developmental spectrum. We have now reached life expectancies as high as 85 in countries like Japan, and many other nations are not far behind.1,4

Research has also shown that life expectancy is likely to continue to increase. The number of people aged over 100 (centenarians) has doubled almost every decade since 1950 within more developed nations.4 Furthermore, Lutz and his colleagues have shown through a series of algorithms that life expectancy will continue to grow within all world regions over the next century.6

However, increased longevity has been accompanied by increased prevalence of disease among the elderly.7 Advances in medicine and improvements in living conditions have reduced mortality caused by infectious and parasitic disease—previously the leading cause of death—which mainly affected children and the young.1,8

However, decreased acute illness has been replaced with reciprocal increases in chronic, non-communicable disease—cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease—in the elderly aged 65 and older.1,9 Figure 3 depicts the increasing burden of chronic disease across low-, middle-, and high-income countries.1

Figure 3: Burden of chronic disease between 2008 and 2030.10

We can see that the prevalence of non-communicable diseases is rising across all groups, and low-income, countries with rapidly ageing populations, are likely to experience the largest increases.

Non-communicable diseases often leads to increased disability and are very expensive to manage due to their long-term nature.1,9 Global surges in the elderly populations and subsequent increases in non-communicable diseases can have costly implications on health systems, which we will discuss later.

Decreased Fertility

Fertility rates have been decreasing since the beginning of the 20th century. More developed countries fell below the population replacement rate of two live births per female by the 1970’s.1 Now, this trend has extended to many less developed countries, so that 44 of them were at or below the population replacement rate by 2006.4 Combining these statistics with global population ageing, more than 20 countries are projected to experience significant population decline by 2030. These include both high-income countries, like Japan (11 million decline), and low-to-middle income countries, such as South Africa (8 million decline).4

There is also an increasing worry surrounding ‘childlessness’, as nearly 20 percent of women in the modern world do not give birth.4,11 Diminishing fertility rates threatens to reduce the workforce and change important family-care structures that will be imperative for an ever-increasing elderly population.

We will explore the global consequences of the concerns mentioned above and how they can negatively impact health and wellbeing.

An Ageing Population: Impacts and Responses

Unless addressed, population ageing is likely to have significant negative impacts on global status. We will focus on two topics at the centre of discourse in relation to this issue:

- Changes to health and health systems

- Changes to workforce and retirement

Health and Healthcare

As previously mentioned, there is a rapidly increasing prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCD) worldwide. Non-communicable diseases are now the leading cause of death. “Of the 57 million deaths that occurred globally in 2008, 36 million—almost two thirds—were due to NCD, comprising mainly cardiovascular diseases, cancers, diabetes and chronic lung diseases.”1 Furthermore, 75 percent of death from NCD occurs in individuals aged over 60, highlighting that the elderly are at highest risk.4

Progress in medicine has improved our ability to detect disease early and extend lives of those living with chronic conditions, but this has come at a cost. Despite some conflicting data, the general consensus is that as our ageing population has accrued greater amounts of NCD, there have also been increases in severe disability.1,7,12 The most dramatic increases have been in low- and middle-income nations, however many high-income countries show this trend as well.1,7 It is predicted that NCDs will lead to over three times as many disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in low- and middle- income countries by 2030.12

A major cause of disability amongst populations with increasing longevity is dementia, the risk of which inclines sharply in the older-elderly population.1 Dementia, along with other NCD, eventually leads to complete loss of function and requires constant care to perform basic daily activities. Ultimately, an increasing disease burden caused by population ageing means that we will have more diseases to manage, over longer periods, with more complex needs. This translates to increasing healthcare costs that can put major strains on health systems around the world.

In more developed countries, where there is no lack of health care services, the access of medical care is positively correlated with age. An overall increase in proportion of elderly individuals with NCD directly correlates to rising healthcare expenditures.1,12 Less is known about the cost-impact of ageing populations on developing nations, however preliminary studies by the World Health Organisation (WHO) show increased prevalence of NCDs is being met by rising medical complications and healthcare costs.1

The WHO have summarised growing concerns in their 2011 report:

Figure 4: Living status of people aged 65 and over in Japan between 1960 to 2000.16

“Long-term care for older people has become a key issue…such care involves a range of support mechanisms such as home nursing community care and assisted living, residential care, and long stay hospitals. While the cost of long-term care is a burden to families and society there are other concerns as well. For example, the staffing needs for caring for aging populations have increased the migration of health workers from lower income to higher income nations.”

Clearly, this has become a transnational problem and in its current state it will only worsen. Growing rates of childlessness results in family structures that are no longer able to offer care to the elderly, with increasing numbers being institutionalised, as has been observed in Japan (Figure 4).4

Additionally, the burden in high-income countries is siphoning healthcare workers from low-income countries, which have faster ageing populations and less healthcare services.

The system is on course to collapse.

There is no doubt that international cooperation and intervention is needed to tackle this complex issue. Much of the proposed strategies have centred around global campaigns to address lifestyle risk factors—diet, exercise, and tobacco use—which have the greatest effects on NCD risk and outcomes.12,13

These interventions might include: increasing international taxes on tobacco and promoting smoke-free zones; media-based promotion for physical activity; and creating policies to regulate salt and fat content in food, especially amongst global fast-food companies that have negatively impacted diet and health globally.12–14

These are not inexpensive or simple to accomplish, however the long-term investment can reduce health costs and vastly outweigh any short-term costs incurred.

Workforce and Retirement

The second major issue concerning an ageing population is regarding a dwindling workforce and increase socioeconomic costs from a surge in pensioners. As the number of elderly persons leaving the workforce and entering retirement has increased, significant strain has been placed on pension budgets and on younger generations who are pressured to work more in order to keep governmental and social programs afloat.1,15

Today, people spend less of their lifetime working and more time in retirement than previously. In 1960, men spent an average of 46 years working and slightly more than one year in retirement. By 1995, due to increased life expectancy and social changes, the average man spent 37 years working and 12 years in retirement.4 Having more elderly people spending longer periods in retirement drains national pension budgets.

As a result, many governments have responded by encouraging a shift to employment pension plans that put greater pressure on individual workers to actively save for their future pension account, rather than passively receiving federal or company benefits after retirement.4

Additionally, decreased fertility and increased childlessness has equated to a shrinking younger generation and workforce.4,15 Concerns are that reductions in the number of younger adults of working age will not only lead to overall declines in productivity, business, and global trade, but also increased pressure to support elderly.4 This is especially worrying for low- and middle-income nations, which lack the federal funds and programs to cover an ever-increasing elderly population.

Ultimately these economic issues have culminated in: higher poverty rates amongst elderly people; lack of pension programs and safety-netting to cover increasing numbers of elderly in less developed countries; and higher taxes for younger, working generations.4,15

The most straightforward solution suggested in response to the economic implications of population ageing is to raise retirement ages.7 Generally, having age limits for retirement and pension fosters a culture where individuals retire as early as possible, despite having the capacity to work longer. Raising the pension age or adopting a system that is based on health-related criteria in lieu of age can slow the rate of pensions and offset some of the economic burden.1

Other critics promote the reintroduction of elderly into the workforce. Creating jobs and training programs to keep the elderly population working longer not only directly helps productivity, but also lessens disease and disability amongst the elderly. Studies show accelerated cognitive decline in those aged 55 to 65 in countries where individuals left the workforce at earlier ages.1

Working part-time jobs that require little physical exertion can help delay cognitive decline and dementia, which lead to significant morbidity and burden of care. It will take significant effort and funds to reform social policy, create new training programs and part-time job markets, and shift cultural attitudes towards postponed retirement and a working elderly cohort.

However, these changes can help decrease economic burdens and benefit all age groups. An increase in part-time jobs will not only benefit the elderly population, but also allow more opportunities for younger people to work more part-time jobs as well; and evidence suggests that shortened working weeks over extended working lives can improve life expectancy and health outcomes.7

Conclusion

Population ageing is a serious global health issue that will have significant socioeconomic and health impacts unless addressed swiftly and aggressively. Although there is still much to be said on the issue that could not be included in this manuscript, we have established implications to health and health systems with the rise of NCD, as well as economic ramifications that can threaten states of wellbeing worldwide. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that population ageing is a transnational issue with global stakeholders and investors. It affects low-, middle-, and high-income countries alike, and the relationship between them, such as with the migration of health workers and changes to business and productivity that may impact trade and global markets.

Moving forward, it is imperative to create international, standardised means of obtaining data on population ageing in regards to the variables we have discussed. There still remain some gaps in data, such as the progression of dementia in lower-income countries, and inconsistencies, such as countries defining ‘elderly’ by different age ranges, which can subvert our understanding of this crisis.1,7

Ultimately, this is a global problem and it will require a global response in order to secure our future for the elderly, the young, and all in between.

______________________________________

WORKS CITED

(1) – World Health Organisation. Global Health and Aging. NIH Publ. no 117737 2011;1(4):273-277. Available at: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0095-9006

(2) – Koplan JP, Bond TC, Merson MH, et al. Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet 2009;373(9679):1993-1995.

(3) – Un Population Division. World Population Prospects: the 2010 Revision. Waste Manag. Res. 2012;27(8):800 -812.

(4) – Dobriansky PJ, Suzman RM, Hodes RJ. Why Population Aging Matters – A Global Perspective. US Dep. State 2007:1-32.

(5) – Kinsella K, Gist YJ. Older Workers , Retirement , and Pensions. US Department of Commerce 1995.

(6) – Lutz W, Sanderson W, Scherbov S. The coming acceleration of global population ageing. Nature 2008;451(7179):716-719.

(7) – Christensen K, Doblhammer G, Rau R, Vaupel JW. Ageing populations: the challenges ahead. Lancet 2009;374(9696):1196-1208.

(8) – United Nations. The Millennium Development Goals Report. United Nations 2015:72.

(9) – Lopez A, Mathers C, Ezzati M, Jamison D, Murray C. Global Burden of Disease and Risk Factors. World Bank. 2006.

(10) – World Health Organization N. The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 update. Update 2008;2010:146.

(11) – Mascarenhas MN, Flaxman SR, Boerma T, Vanderpoel S, Stevens GA. National, Regional, and Global Trends in Infertility Prevalence Since 1990: A Systematic Analysis of 277 Health Surveys. PLoS Med. 2012;9(12):1-12.

(12) – World Health Organisation. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases. 2010:176. Available at: http://www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd_report_full_en.pdf.

(13) – Beaglehole R, Yach D. Globalisation and the prevention and control of non-communicable disease: The neglected chronic diseases of adults. Lancet 2003;362(9387):903-908.

(14) – Chaloupka FJ, Straif K, Leon ME. Effectiveness of tax and price policies in tobacco control. Tob. Control 2011;20(3):235-238.

(15) – Campbell R. Population Decline and Ageing in Japan: The Social Consequences. Pac. Aff. 2008;81(3):471-472.

(16) – Research NI of P and SS. Population Statistics of Japan 2003. Popul. Stat. Japan 2003 2003. Available at: papers2://publication/uuid/A76E89DC-5803-4D9C-9968-D4E8CA180595.