Resisting Resistance: Tackling Multi-Drug Resistant Tuberculosis

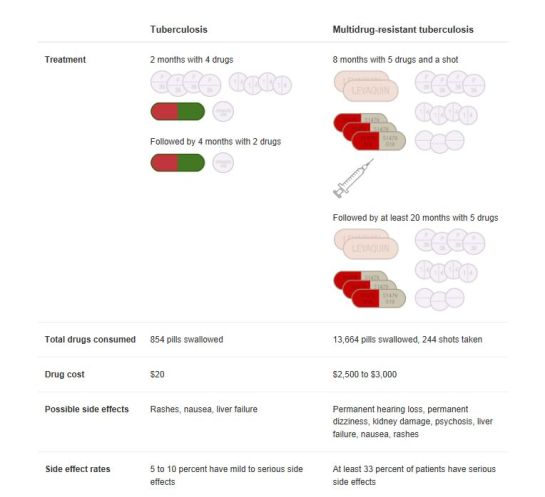

In an NPR article published last month the following table was used to highlight the stark contrast in treatment plans between “regular” Tuberculosis, and what is known as ‘Multi-Drug Resistant Tuberculosis’ (MDRTB).

As the chart indicates, the latter is a much stronger form of the normal disease, which has become mutated so that first-line drugs no longer work to eradicate the virus in patients. This poses dire consequences; such super-forms of disease carry with them higher rates of mortality, as well as an increased financial burden.

The factors allowing for highly resistant forms of disease to propagate and proliferate are multidimensional—resulting from a mix of biological, social and economic conditions. The situation in Russia serves as a good case study for understanding what conditions could have led to such situations. In his novel Pathologies of Power, Dr. Paul Farmer recounts his experience working with Russian prisoners infected with Tuberculosis. He assures that lack of space, nutrition and consistent access to medications form a trifecta allowing for MDRTB to develop. Russian prisons (like the majority of prisons in the world) are all too often overcrowded, with poor sanitary conditions to boot. Close proximity means that an individual who contracts the virus can easily spread it to fellow inmates and onwards. As Dr. Mel Spigelman stated in the NPR piece: “TB requires relatively close contact for transmission. You really need to be around somebody for a good amount of time.”

While the cramped quarters explain how the initial transmission of TB is spread throughout these prisons, the change from TB to MDRTB is cause of a more complex issue. Referring back to the chart above, we can see that the treatment of TB is not only possible, but also rather straightforward. Normally TB can be cured using first-line drugs within 6 months at a rate of about $20 USD per person. This is all assuming of course, that you have 1) have access to medication; 2) have the capital to afford those medicines (according to the World Bank, those living in developing countries live on less than $1.50 a day); and 3) take the time to finish the treatment to completion. However, all three of these factors pose great challenges to the situation in Russia.

Continuity, both on the medical-supply end and the patient-compliance end, is a major barrier to overcome. Farmer continuously stresses the difficulty healthcare workers in prison clinics encountered when trying to secure medication for their patients—most often to no avail, due to a lack of financial resources. An inconstant and relatively costly drug supply combined with the transient nature of prisoners, who might serve their sentence and leave, equates to sporadic treatment that allows the virus to grow immune to the medication between the long gaps in medication. And if regular TB medication was difficult to secure in the first place, you can imagine how much harder, if not impossible, it would be to obtain the drugs needed for MDRTB, which takes 4 times as long to treat with double the amount of drugs.

We must also take into account those prisoners who say develop MDRTB in prisons and then are released after their sentence; not only is it even less likely for them to encounter the proper treatment regimen through national medical channels, but they also run the risk of further spreading the disease in the public community. That is not to say the prisoners are solely responsible for the spread of MDRTB Russian communities. While we were using prisons as a prime example, the truth is that it is not very hard to find other communities or areas with cramped living conditions, poor sanitation and lack of medication. Many low SES communities and ghettos share these same challenges, which also puts people living in those areas at high risk for contracting TB and MDRTB.

Moves are now being made to combat MDRTB, as well as the normal strain of TB before it has a chance to develop into the resistant form. Groups like Sputnik, a mobile healthcare group that travel through Russian cities locating cases of TB and providing those individuals with care, may have what it takes to start reversing the status quo. The unique (and most successful) aspect of Sputnik is that it offers culturally relevant solutions. Nurses and health workers in the group are trained to keep tabs and follow-up on individuals at risk, who are living in unstable, resource-poor settings—many of whom have prior histories of heavy drug use and other self-destructive habits.

However, the strict treatment regimen along with personal hardships, leave many of these individuals frustrated and overwhelmed by the process. An NPR article highlighted the trials faced by Sputnik staff, stating that “some patients get fed up with their treatment before it is complete…They resist, they hide, they lock their doors to avoid the Sputnik team.” That being said, it is crucial for the team to get to know the stories of the people under their care, and learn who they are as a people, not just as a “patients” in need of medication. Doing so builds up a relationship and trust, which increases the chances of compliance to treatment and overall successful outcomes.

Still, there remains much work to be done. In 2010 the WHO announced that MDRTB reached record-breaking levels globally. Moreover, even stronger, more resistant forms of the virus have now been observed with cases of Extensively Drug-Resistant TB (XDR-TB), which do not even respond to most second-line drugs. Russia has actually proven to become a paragon in initiating efforts to lower rates of MDRTB, despite the challenges that remain. Considering that over half the cases of MDRTB occur in China and India, only a fraction of which are actually diagnosed, it is time for the international community to reenact strategies used by groups like Sputnik to help contain and eradicate MDRTB world-wide.